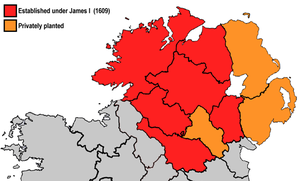

| A map highlighting the areas subjected to British plantations in Ulster, using modern county boundaries. (Photo credit:Wikipedia) |

‘For God’s sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country.’ Visiting Northern Ireland as home secretary in 1970, Reginald Maudling, whose mellow moderation verged on a slothful desire for an easy life, was understandably exasperated by the Ulster problem – but no more so than a long line of politicians, before and since. Churchill – not so easily depicted as a faint-heart – lamented in the aftermath of the First World War that, while the cataclysm had transformed the rest of Europe, the Ulster question remained as intractable as ever and politicians would once more have to pay attention to the ‘dreary steeples of Fermanagh and Tyrone’.

Fifty years and another world war later, Ulster remained a needling presence in British political life. At the time of the Ulster Workers’ Council strike of 1974, which helped bring down the cross-community power-sharing executive agreed at Sunningdale in 1973, a peeved Harold Wilson openly denounced Ulster Protestants as ‘people who spend their lives sponging on Westminster and British democracy’. The prime minister’s accusation riled the Protestants, who thought themselves harder-working than their feckless Catholic neighbours, the real spongers in their eyes. Incensed Ulster Unionists began to sport sponges on their lapels.

Are the people of Ulster – as its Protestant champions claim – an integral part of the British nation? Or is Northern Ireland rather, as Irish nationalists insist, a relic of empire, whose close proximity to Great Britain obscures the otherwise bald fact that British colonialism is the ultimate cause of the modern Ulster Question? Both claims are valid, while neither tells the whole story. Certainly, the Northern Irish problem has its roots in a colonial project, the Ulster Plantation of the early 17th century. Yet with the passage of the Act of Union between Great Britain and Ireland in 1800, the north-eastern counties, with their Protestant majority, became the most self-consciously British region of the United Kingdom. By the same token, Britishness of the Ulster kind – Orange parades and kerbsides painted red, white and blue – seems demonstrative and stridently un-British. To the summer visitor from Britain who pulls off the ferry at Larne, the proliferation of Union Jacks along roads and at roundabouts is alienating. Unintentionally perhaps, the puffed-up hyper-Britons of Ulster exhibit colonial insecurity and make clear the precariousness of their position on what its current first minister, Peter Robinson of Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party, once described as ‘the window ledge of the Union’.

A colonial strangeness lurks behind such seemingly familiar phenomena as student drunkenness. Belfast’s Holy Land is an area between Queen’s University and the Ormeau Road where the streets, built by a biblically minded Victorian Protestant, are named for Jerusalem, Damascus and Carmel. Originally, Protestants lived here, and later, the area became more mixed, with young lecturers bringing in a dash of counter-culture; but in recent years the Holy Land has become a place of student-dominated multiple-occupancy housing and raucous anti-social behaviour, which tends to culminate in riotous stand-offs with the police on St Patrick’s Day. The authorities would rather not confront the fact that many of the rioting students – ‘culchies’ (yokels) from mid-Ulster – wear Celtic tops or Gaelic Athletic Association shirts, and are asserting an instinctive quasi-sectarian command of what is now their territory. Protestant students prefer to rent accommodation further south in Stranmillis.

In Belfast the urban motorway – something that has done much to blight city life across the United Kingdom – has a sinister, though not altogether unhappy significance. As Dominic Bryan argues in his lively essay in Belfast 400, the M2 and the Westlink have served as a bleak cordon sanitaire between some of the rival sectarian ghettoes in the west of the city. Moreover, as the security forces were quick to recognise, the limited number of crossing points for vehicles meant that the centre of Belfast could be more effectively secured against disturbances spilling over from the Shankill and Falls Road areas. This estrangement persists, long after the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. Peace did not bring the ‘peace walls’ tumbling down, or strip away the protective netting which covers tiny back gardens within lobbed-bottle distance of the other community.

Ulster is, and remains, a collage of confessional territories. As the late A.T.Q. Stewart remarked in his history of Ulster, The Narrow Ground (1977), every resident of the province carries around in his or her head a complex and detailed geography: they know which villages or streets are Protestant or Catholic, or mixed. These internalised microgeographies – of small urban pockets such as Sandy Row or the Short Strand – provide the matter of sectarian conflict, for, as the acerbic historian Joe Lee lamented, Ulster has a ‘dearth of major atheist settlements’.

Geography also presents challenges on a larger scale. The incomer from ‘GB’, as Ulster folk call Great Britain, quickly learns not to call the nearby larger island ‘the mainland’, while apparent synonyms for Northern Ireland – such as ‘Ulster’ or the ‘Six Counties’ or ‘the North of Ireland’ – betray the politics and religion of the speaker. Where, indeed, is Ulster? This seemingly straightforward question opens up a rich seam of history. Ulster is one of the historic provinces of Ireland, and comprises nine counties, six of which – Armagh, Down, Antrim, Londonderry (or Derry), Fermanagh and Tyrone – are today in Northern Ireland, and three – Monaghan, Donegal and Cavan – in the Irish Republic. The colonial Plantation of Ulster in the reign of James VI and I covered six counties, but not those of today’s Northern Ireland. Ironically, the counties which became the redoubt of British Protestant settlement – Antrim and Down – were not technically part of the Plantation, which instead encompassed Donegal (then known as Tyrconnell), Londonderry, Armagh, Cavan, Fermanagh and Tyrone.

During the Home Rule crisis of the early 20th century, Sir James Craig, the founding father of Northern Ireland, envisaged hiving off the four most strongly Protestant counties – Antrim, Down, Londonderry and Armagh – to form an Ulster statelet. In the event, Fermanagh and Tyrone were added to the new self-governing province of Northern Ireland established under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, but Article XII of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, between the United Kingdom and the Irish Free State, was deliberately vague on the future resolution of the border. In the event, the proposal of the Boundary Commission of 1925 to shave off southern Armagh for the Free State and transfer parts of eastern Donegal to Northern Ireland was much too controversial to implement, or even acknowledge in public.

Certain areas near the border in Armagh became notorious for atrocities more than a century before there even was a border. Uncanny congruences of this sort reinforce the assumption of outsiders that Ulster is a land of memory, where the horrors of an inescapable past forever haunt the present. However, as Sean Connolly notes more precisely in Belfast 400, memory is all too often selective memory, if not ‘historical amnesia’. When 19th-century Belfast became ‘the capital of Irish Unionism’, its citizens conveniently forgot that in the 1790s the city had been ‘the birthplace of a United Irish movement committed to the establishment of an independent Irish republic’. At the centenary of the Rebellion of 1798, the leading officials of the Orange Grand Lodge of Belfast misremembered the largely Presbyterian rising in Ulster as ‘a series of most foul and cowardly murders and massacres of innocent men and women whose only offence was their Protestantism’. James Loughlin notes in his essay in Ulster since 1600, that ‘former Presbyterian rebels’, keen in the early decades of the 19th century to reinvent themselves as loyal Britons, were ‘only too ready to frame the rebellion through the lens of 1641 as a vast Popish conspiracy’. In other words, although Ulster Catholics had been largely quiescent in 1798, the supposed history of the rebellion was cunningly – but convincingly – turned upside down to fit with an existing memory of the Ulster Catholic rising of 1641 (and, to be fair, with the strikingly different pattern of hostilities in other parts of Ireland during 1798).

Moreover, an entrenched rhetoric of civility and barbarity, which dated back to the Ulster Plantation, and beyond, appeared to confirm such perceptions. After the flight to the Continent in 1607 of the harassed Gaelic earls – Hugh O’Neill, Second Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donnell, First Earl of Tyrconnell, along with Cúchonnacht Maguire, Lord of Fermanagh – the Plantation of 1609 was designed to bring civility to these rude parts. The new king, James VI and I, had already attempted to colonise the fringes of Scottish Gaeldom with civilising Lowlanders, as Martin MacGregor’s essay in the collection edited by Eamonn O Ciardha and Micheál O Siochrú makes clear. From Giraldus Cambrensis to the chronicler John of Fordun, medieval commentators from Britain had demonised the Gaels for their barbarous ways. Such sentiments still persist in the expected quarters. Ian Paisley claimed in the early 1980s that the forebears of the good Protestant folk of Ulster had ‘cut a civilisation out of the bogs and meadows of this country’, while the Gaels ‘were wearing pig-skins and living in caves’. These Yahoo Gaels were not only uncivilised, but so addicted to violence that it had permeated their entire culture. Paisley’s daughter, Rhonda, at one stage a Belfast councillor, complained that the Irish language itself ‘drips with their bloodthirsty saliva’.

Although there was a Scots presence in the north-east of Ireland from the early 17th century, Scots Presbyterian culture wasn’t consolidated there until the arrival of General Robert Munro’s Scots Covenanter army in the 1640s. The Scottish famines of the late 1690s brought a further exodus to Ulster of Scots, particularly from the south-west, the stronghold of Covenanting Presbyterianism. The Scots Covenanters were decidedly not republicans; they preferred to be governed by kings, but owed them a highly conditional allegiance. If the king failed to uphold the community’s Covenant with God, then the people were entitled to take up defensive arms against his malignant rule, and in certain circumstances even to execute divine vengeance on the apostate ruler. It is ultimately from this branch of the Scots Presbyterian tradition that Ulster inherits the peculiarities of loyalism, a commitment to queen and country so anarchic and tenuous as to be downright disloyal.

Loyalism has taken different organisational forms. The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) was set up in the mid-1960s by a former British soldier called Gusty Spence, as a proactive means of combating the upsurge in IRA activity which, it was expected, would follow the fiftieth anniversary in 1966 of the Easter Rising. The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) emerged in the early 1970s as a form of vigilantism by the Protestant working class against the insurgency of the Provisional IRA (which had split in disgust from the torpid Marxism of the Official IRA in 1969). The UDA used a proxy, the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF), for its terrorist activities. So self-defence was followed by the unprovoked sectarian killing of Catholics – regardless of whether they had any links with the Provos – and eventually, in some areas at least, by psychopathic gangsterism. Clearly, there is a major cleavage within Ulster Protestantism between Unionism and loyalism, but it’s not easy to trace its course.

Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) once stood on very uncertain terrain between the ‘big house Unionism’ of the old Ulster gentry, from which it recoiled, and a proletarian loyalism it sometimes appeared to court. How was one to interpret Paisley’s night-time rally on a hill in County Antrim in 1981, at which five hundred supporters waved their firearms licences? The Paisleyites’ reckless disregard for the rule of law, for Westminster and for British constitutional norms earned them the contempt of Enoch Powell, a Conservative turned Ulster Unionist, who favoured the full integration of Northern Ireland into the UK. Powell claimed Paisley and his followers were ‘Protestant Sinn Féin’.

The distinction between Unionism and loyalism revolves not only around violence and the nature of Ulster’s commitment to the British state, but also around class – that omnipresent yet largely invisible factor in Northern Irish politics. Loyalism has been an underappreciated expression of working-class consciousness. Andy Tyrie, the supreme commander of the UDA between 1973 and 1988, admitted that challenging the dominance of Unionism was an important part of being a loyalist. Of course, loyalism was an uninhibited demonstration of anti-Republican hostility, but it was also a form of resentment against the middle-class Unionists in their leafy suburbs, who seemed content enough to let their proletarian co-religionists bear the brunt of the internal struggle with the Provos.

Why, an outsider might ask about the situation in Ulster, did the region fail to develop the same class-based politics as the rest of the UK? Northern Ireland seems to be stuck in a conservative limbo, with voters preferring to vote along religious lines without regard to their material interests. But this analysis is oversimplified. Ulster is, in fact, rather left-wing. In one of the most surprising essays in Ulster since 1600, Graham Brownlow calculates that, factoring out coal and iron and steel manufacture, which the province lacks, Northern Ireland was ‘much more strike-prone than the UK average’ between the 1940s and the mid-1980s. UK trade unions enjoy considerable support, in spite of the divided national allegiances of the workforce. Indeed, Northern Ireland has a higher density of trade-union membership – that is, actual membership divided by total potential membership – than other parts of the United Kingdom, including Labour’s heartlands in Wales and Scotland. The Northern Ireland Labour Party, established in 1924, had offered an appealing alternative to ethnic politics, but just as it had emerged as the official opposition in Stormont it was overwhelmed by the onset of the Troubles. Similarly, the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) – formed in 1970 out of various groupings, including the Republican Labour Party, and supported by some former members of the Northern Ireland Labour Party – shed its Labourite origins under John Hume’s leadership, but could not present an Irish enough identity to see off the electoral challenge of Sinn Féin. In any case, people in Ulster might wonder whether they needed class-based political parties. Sectarianism had done more to protect the working class in Northern Ireland than a powerless Labour Party had achieved in Britain after 1979. The Troubles helped to keep Thatcherism at bay, so that in 1989 the journalist Ian Aitken could describe the province as ‘the Independent Keynesian Republic of Northern Ireland’.

Here the middle classes flourished during the Troubles, their high-living maintained by a bloated public-sector-cum-security-state. The North Down constituency is a haven of peace and material amplitude, though notorious in cliché for its all too stark social division between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-yachts’. Nothing is as likely to shock the preconceptions of the visitor who comes to view the grim locations of ‘Troubles tourism’ as the sight of Ulster Tatler on newsagents’ shelves. Middle-class life in the province has its own variations. South Belfast has a multicultural bohemian flavour, as obvious in the boutiques of the Lisburn Road as around Queen’s University itself. This is a world captured with deliberately baroque exaggeration in Chris Marsh’s comic novel A Year in the Province (2008), whose humour comes from a pitch-perfect rendering of the cadences and sing-song inverted repetitions of Ulster speech. Ian Sansom’s deadpan novel Ring Road (2004), on the other hand, explores the dour and parochial absurdities of Ulster’s less flashy middle classes in the dormitory towns around Belfast.

While the Troubles did very little to threaten the middle classes, events have recently taken a potentially worrying turn. The recent spasm of unrest was provoked by Belfast City Council’s decision in December to restrict the flying of the Union flag at the City Hall – it had always flown there year-round – to selected dates in the political calendar, such as the Duchess of Cambridge’s birthday. The decision was not just the doing of Sinn Féin, but was supported by the somewhat priggish middle-class do-gooders of Alliance, a political party which has traditionally floated consequence-free above the streetfighting of proletarian Ulster. On this occasion, however, loyalist protesters chose to single out Alliance for facilitating the outrage. The party offices and the homes of prominent Alliance politicians became targets. The riots which have followed have been blamed – rightly – on loyalist recidivism.

There is, however, another unexpected side to loyalism, as Peter Shirlow’s book demonstrates. Whereas middle-class Unionist Ulster was for decades happy enough to say no, time and again, to changes in the government of the province, working-class loyalists – despite their own reputation for intransigence – could not afford to indulge in the same endless rejection. Shirlow distinguishes between the ‘idiocy’ of rejectionist loyalism and an avant-garde of ‘progressive’ or ‘transitional’ loyalism willing to engage with the demands of the Catholic community and to think imaginatively about conflict resolution. Working-class loyalists experimented – long before their snooty Unionist cousins – with a ‘non-sectarian mode of Unionist politics’, which recognised the shared sufferings of working-class Protestants and Catholics alike.

In 1979 the UDA-backed New Ulster Political Research Group published a report called Beyond the Religious Divide, which explored the common ‘Ulster’ identity of the province’s Catholic and Protestant peoples. The UDA also flirted with the idea of an independent Northern Irish republic as an ingenious solution to the underlying cause of the Troubles, namely the rival British and Irish claims of sovereignty. In 1987 the Ulster Democratic Party (UDP), which would become a front for the UDA, put out Common Sense, which called for power-sharing and equality across the sectarian divide. The hard men of the UVF also caught the peace and reconciliation bug. In 1984 the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP), the political wing of the UVF, proposed a Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland, which was too daring for the authorities, and followed it up with an ecumenical document entitled ‘Sharing Responsibility’. Needless to say, not all loyalists were impressed. Transitional loyalists were seen by traditionalists as ‘lundys’ (the Ulster Protestant term for ‘quisling’). Another grouping, the Loyalist Volunteer Force, denounced the PUP as ‘atheistic communists’ determined to impose ‘a socialist ideology over a conservative people’.

This is, of course, to beg the question. Ulster has an ingrained conservatism, to be sure, but also an old-fashioned socialism about which it often seems to be in denial. The future remains uncertain. The dispute about the flag shows how much symbols matter in Northern Ireland, and unfortunately Ulster has just embarked on a ‘decade of centenaries’. Some are uncontentious, such as the four hundredth anniversary of Belfast’s receipt of a royal charter in 1613 and the Titanic centenary of 2012; others are pregnant with menace. The contrasting blood sacrifices of Dublin’s Easter Rising and the Ulster Division’s losses in the Battle of the Somme loom ominously in 2016. And, if we get past them without incident, the centenary of the Protestant statelet itself and the partition of Ireland arrive in 2020-21.

By Colin Kidd.

Winston Churchill wrote: “The power of the Executive to cast a man into prison without formulating any charge known to the law, and particularly to deny him the judgement of his peers, is in the highest degree odious, and is the foundation of all totalitarian government, whether Nazi or Communist.”

No comments:

Post a Comment